A guest post for the Moving Blog by DJ John Armstrong, who selected the tunes for our Moving Conversation 2 after-party on January 12th. John has recently put together a 4-CD box set of essential zouk both traditional and contemporary, spanning the years from the late 70s to today. You can find it here, amongst other internet places:

Simply Zouk. If you’re still one of the intrepid few who prefer to buy their music in a physical shop, you’ll also find it at HMV and similar retailers. Thank you, John, for the music, your knowledge, and the post!’

A while back, I was invited to start work on a music compilation of traditional French Antillean music: gwoka, bele, chouval bwa, biguine, jing-ping, and so forth. I needed some quotable contemporary material from current traditional musicians, and found to my surprise that those approached would only participate if the interviews were conducted in kreyol.

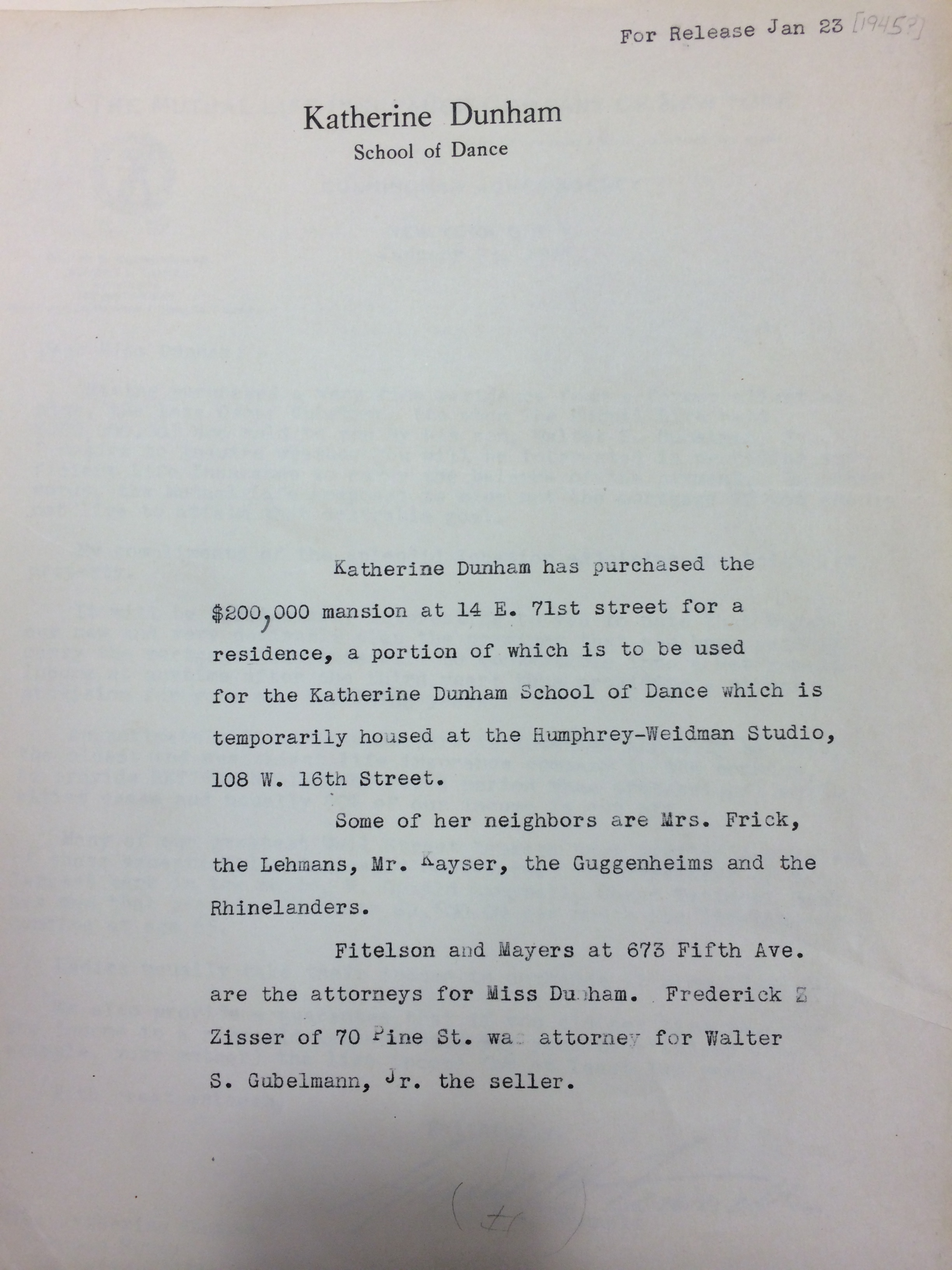

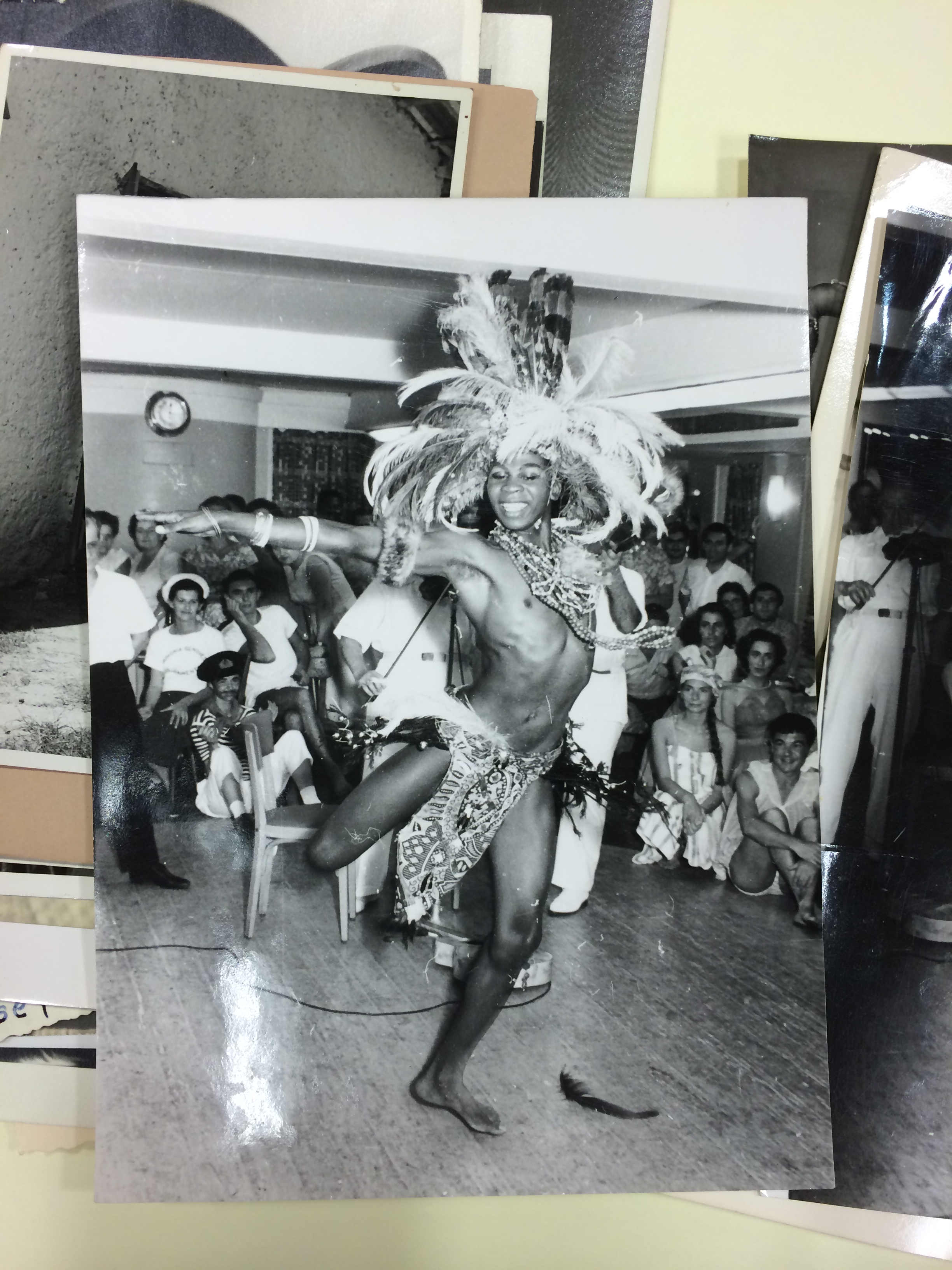

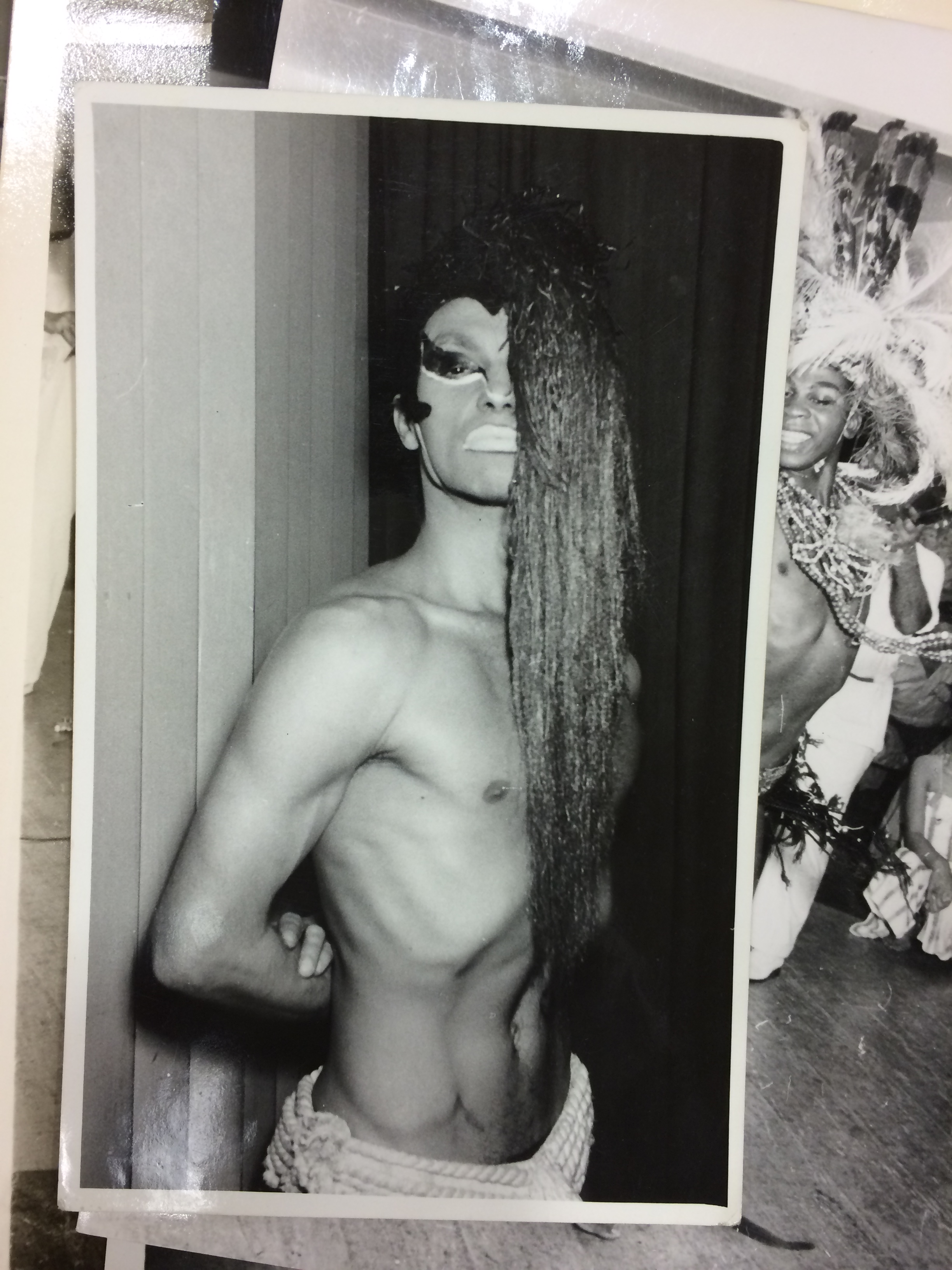

For commercial reasons the compilation wasn’t completed. But the illuminating conversation between Prof Carolyn Cooper and Jocelyne Beroard at January’s Moving Conversation, as well as the wonderful performance by Zil’oKa, a dance group whose average age can’t be more than the early 20s, reminded me that it was in the fields of language and dance just as much as of music that Jocelyne’s band, Kassav’, helped effect a revolution.

Francophone songwriters have been composing in kreyol for more than half a century, true, but it wasn’t until the late 70s and early 80s that there was general commercial recognition of the fact. Suddenly, LPs from the French Antilles and Haiti started appearing in record-shop racks with pull-out lyric sheets in (to many eyes) an almost-indecipherable script. Kassav’s members, and the composers with whom they collaborated, regarded it as a mark not of nationalistic honour, but of cultural necessity that written lyrics accurately reproduced sung lyrics.

In this, Kassav’ were very much of their time as regards contemporaneous writers in fields other than music. The Negritude writers of the 30s- Aime Cesaire and others- had already extended the scope of the linguistic studies of the Haitian anthropologist Antenor Firmin beyond specialist circles and into wider cultural usage. But it wasn’t until the 70s and 80s, and the appearance of Martinican authors, poets and movie scriptwriters such as Raphael Confiant, Daniel Maximin, Jean Bernabe and Patrick Chamoiseau that kreyol — as a signifier — became almost an everyday necessity rather than an academic nicety, even though such writers were not confining themselves purely to kreyol in all their work.

The same thing’s happening today in Jamaica, although admittedly, reggae has had a much wider world stage for a much longer time than Franco-Caribbean music. Prof Cooper played a track from the recent album by perhaps the most exciting ‘new’ reggae voice in a decade — Chronnix. Just 22 years old, Chronnix is part of a new generation of Jamaican artists that don’t recognise the constraints and conventions of commercial reggae and dancehall. Accordingly, you’ll find lovers’ rock, dub, ragga, dancehall, roots, Rastafari, nyabinghi and everything in between in a Chronnix set, all of it composed in a contemplative and poetic patois, with thematic preoccupations that owe more to Bobs Dylan and Marley than to current dancehall.

What’s more, written Jamaican patois is appearing more often now than a decade ago: for example, in the extraordinary novels of Marlon James, such as A Short History Of Seven Killings, a 700-page, patois-Pynchon-esque mix of fact and fiction about the events and characters surrounding the attempted assassination of Bob Marley in 1977. And here’s the thing: after fifty or so pages, even a white, middle-class English guy like me finds himself internally vocalising and appreciating the flow, beauty and humour of Jamaican patois, and understanding every word.

Here’s a good podcast of current “Reggae Revival” as the ‘new’ Chronnix sound is being tagged.

What’s just as exciting is the way in which Kassav’s ‘kreyol-and-proud’ legacy, as well as the tempos of modern r & b and dancehall, has influenced nouvel’ scene Franco-Caribbean music, as Guadeloupe’s foremost practitioner of back-to-roots modernity, Admiral T, demonstrates below:

Admiral T says to the kids at the beginning: “Mis ti krik!’. They reply ‘Mis ti krak!’ .‘I’m going to tell you a story!’ ‘ Yes, we’re listening!’

Or the beautiful Lycinais Jean, in this adaptation of a Jocelyne Berouard classic:

Q: WHEN IS ZOUK NOT ZOUK?

A: WHEN IT’S BAD ZOUK.

There’s been much discussion among ‘old-school’ Antillean zouk fans about ‘modern’ international zouk (ie post- 1995 or thereabouts). Many believe the current style for the relentless 88-ish b.p.m. tempo is a travesty of original zouk –- party and carnival music which often hit 140-150 b.p.m. in its late-80s heyday. It doesn’t really trouble me either way: after all, much of zouk’s early impetus came from Dominican cadence-lypso and Haitian konpa direct, neither of which styles were unusually frantic.

Nevertheless, I can sort of see why first-generation zoukeurs feel that ‘their’ music has been hijacked by the requirements of the dance teacher! But ultimately, all popular music tends to change in line with the recording techniques and technical advances of the day, and with the blueprint of commercial ‘chart’ music generally. For example, what the music industry calls ‘r & b’ today would be unrecognisable to the r & b artists of the late 40s, like Roy Brown and Wynonie Harris -– but it’s still r & b, for all that.

To reiterate a cliché: there are just two kinds of music, good music and bad music. I think the same applies to zouk, whenever it was recorded.

SEMBA AND KIZOMBA- PAULO FLORES- A TRUE ORIGINAL

Speaking of ‘international’ zouk, I believe that there’s a misconception among some that today’s zouk sound developed solely from Antilllean zouk, and that everything else is mere emulation. The fact is, though, that the Luso-African community had a much larger input into zouk’s beginnings in Paris than they’re often given credit for. There’s something about Luso African melody that makes it perfect for zouk, especially its fado-inflected melancholy.

I recently put together a 4-CD box set of essential zouk both traditional and contemporary, spanning the years from the late 70s to today. You can find it here.

I recall seeing many posters for Cape Verdean parties and club-nights in 80s Paris record shops. More importantly, arrangers and composers such as Emmanuel ‘Manou’ Lima and Tito Paris were providing the blueprints for the then-new sound of zouk-love. Many of the great Afro-zouk classics recordings by Oliver N’Goma, Monique Seka, and others bore the unmistakeable print of Manou Lima’s keyboard arrangements, while the Paris and Abidjan dance club soundtracks of the time included many tunes by Luso-African stars — Bonga, Paulo Flores, Tropical Band, Carlos Burity, Eduardo Paim, Juju Delgado, Cabo Verde Show — in the mix among the more instantly recogniseable Kassav’, Kanda Bongo Man, etc.

Which brings us neatly to the much-anticipated Modern Moves conversation between Paulo Flores, the undisputed king and foremost international populariser of Angolan semba and kizomba and Professor Marissa Moorman, whose book Intonations is the essential primer for any Angolan music lover or musicologist. With that in mind, I thought I’d leave you with a couple of YouTube videos that demonstrate beyond doubt the mutual indebtedness of the Antillean and Luso African musical diasporas.

The first is a duet between Kassav’s Jacob Desvarieux and the great Eduardo ‘General Kambuengo’ Paim.

The second between Jacob, once again, and one of the lesser-known stars of kizomba, Nilo Carvalho.

The third link, of course,, shows Paulo Flores singing one of the keynote songs of semba, with a superb band.

So, till then: We ou nan pati la! E ve-lo na festa!

JOHN ARMSTRONG

Feature image: Zil’oKA dancers performing to ‘Zouk la si sel medikaman nou ni’ in the presence of Jocelyne Beroard and Carolyn Cooper, King’s College London, 12th January 2015. Photo courtesy of Fareda Khan.