It´s not possible to write a series on houses of African music for dancing in Lisbon without giving a special place to the most emblematic and internationally known place: B.leza, the survivor of the tradition of live music. Following the tradition that started in the seventies with Bana´s place, live music is the main raison-d´être of this mythical house.

The name chosen, “B.leza”, has an extraordinary symbolic meaning for Cape Verdean music: B.leza is the artistic name of Francisco Xavier da Cruz (1905-1958), a composer and musician who inspired the musical genre called morna (Cidra, 2010a). His house became the meeting point of artists, and he trusted in Bana to keep by heart his last poems (Cidra, 2010b). If we take into account that Alcides, Bana´s son, is one of the co-owners, we can understand how strong and deep is the relationship of B.Leza to the transnational links between Cape Verde and Portugal.

For all these reasons and more, B.leza can be considered an institution in Lisbon and it deserves an in-depth ethnography: the symbolism of the space, the artists that wrote the history of music, the personages that circulated and still can be found there, the dancing bodies that still respond to the ritual call of music… If we look carefully at B.leza´s dancefloor, we can see how all this long and deep history is embodied through the most pleasant and smooth of movements.

The tradition of live music in Lisbon

Bana was probably the first musician who opened a space in Lisbon for displaying his art and inviting other artists to play. It was in 1976, and the first name given to it was “Novo Mundo”, that later gave place to “Monte Cara” (Cidra, 2010b, INET-MD). Its final name was “Enclave”, the most remembered nowadays. Anyway, it was popularly known as “Bana” on behalf of the famous owner´s name. He put together live music, food and a dancefloor: this formula met with great success. Other well-known artists opened live music venues, such as Tito Paris and Dany Silva. In this context, José Manuel Saudade e Silva, a Portuguese gentleman who worked as a lawyer, fell in love with African music and enjoyed socializing with musicians. One day, he decided to gather some friends to open a new space devoted to this music and dance culture: in 1987 the dance club Baile was born in the ballroom of an ancient palace (XVI century) to give it new life. We are speaking about the emblematic Palácio Almada de Carvalhais. Previously, it had hosted the mythical Noites Longas (Long Nights) organized by Zé de Guiné, one of the fathers of Lisbon´s African nightlife. Among the legends that circulate around the dancing rooms, it is said that it was the place where Marquês de Pombal designed the reconstruction of the city of Lisbon in the eighteenth century! It was some years later, in 1995, that the house would be reopened with a new name: B.leza was born to become an icon that is still alive today.

B.leza, an icon of African-ness in Lisbon

Those who were lucky to live during those times describe the old days with emotion and agree that there are no words to define what it meant: the ancient candelabras hanging from the high ceiling, the corridors where you could find the big stars of African music chatting and smoking, the impressive dancefloor, the mix of solemnity and decadence because of the passing of the years, and the magic of the ambience. It was the meeting point for artists of every genre and intellectuals, and it became the university of African music and culture for those who were interested in it. All the big names of African music played in B.leza: Bana, Bonga, Justino Delgado, Tabanka Djaz, Tito Paris, Don Kikas, Sara Tavares, Lura, Nancy Vieira, just to name a few. DJ Sabura, one of the DJs that you can find there making people happy every Sunday, speaks about the old B.leza as his place of initiation into dance:

“B.leza is a cultural icon of African-ness in Portugal, in Lisbon (…) It was a place that had a mysticism that transpired the walls. There were verses written on the walls, there were red giant candelabras of high value, there was a dancefloor in darkened wood, there was a giant ceiling (…) and apart from the main hall, there were all those narrow corridors where people went to smoke and chat. It was a place where you could find painters, writers, singers, musicians, everyone spoke about it…it was a really special place, and it had a spectacular energy. Everyone was there, look, my initiation into dance took place there, with the friends I met at B.leza.” (Interview with DJ Sabura)

Nevertheless, it was not only about music: from the first day, the vocation of the house was the promotion of African culture (and not only) in all its dimensions: there were also poetry recitations, film exhibitions, visual art exhibitions, and more. Although it has always been open to art from all PALOPs, Brazil, and beyond, B.leza’s fame rests on its special relationship with Cape Verde, to the point that the President of Cámara Municipal de Lisboa (local government of the city) said once that the house can be considered “one more island of Cape Verde”. The owners insist that B.leza is not a disco: it is a house of culture. In fact, the first thing that strikes any lover of African culture is that the house offers a luxury cultural programme for inexpensive (sometimes even merely symbolic) prices.

B.leza, a love story

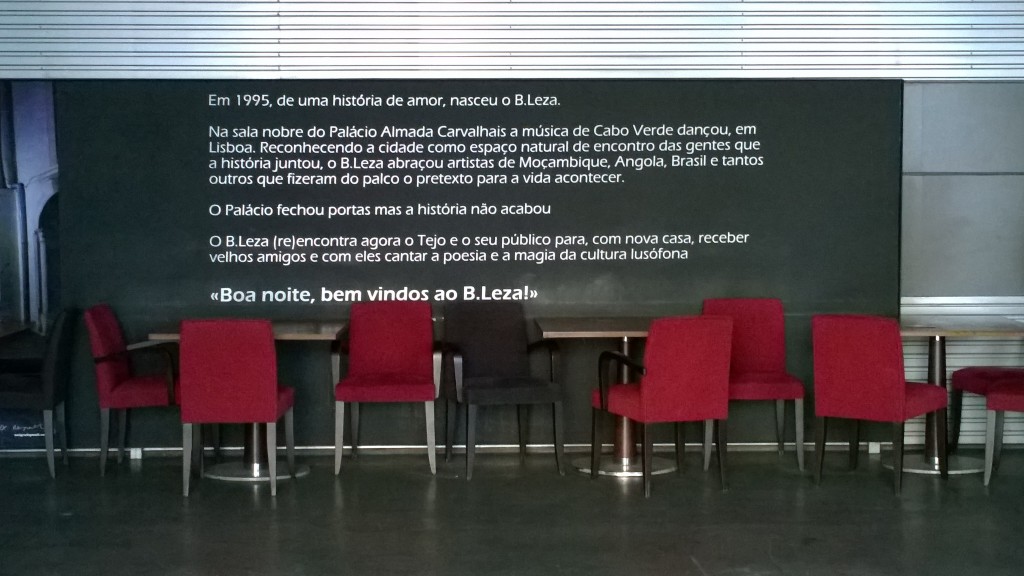

If we go to the dancefloor, we can read this message on the wall: “In 1995, B.leza was born from a love story. In the noble hall of Almada Carvalhais Palace, the music from Cape Verde danced in Lisbon. Recognising the city as a natural space of encounter of the people that History joined together, B.leza hosted artists from Mozambique, Angola, Brazil and many others that made of the stage the pretext for life to take place. The Palace closed but the history didn´t end. B.leza (re)encounters now the river Tejo and its audience to receive old friends with a new house, and sing the poetry and magic of lusophone culture with them. Good evening, welcome to B.leza!”

What is this love story that this welcoming message tells us about? An interview with Sofia, one of the co-owners of the place, leads us to the answer. The magic of D. Jose Manuel Saudade e Silva´s dream was imperilled when he unfortunately passed away in 1994. It was then when his two daughters, Sofia and Magdalena, two strong-minded and determined Portuguese ladies, decided to carry on with their father´s dream as an act of love for him. The musician Alcides (Bana´s son) joined them in the adventure. And they succeeded, there´s no doubt! Now we know the mysterious love story that the walls of today’s B.leza tell us about…

The opening of B.leza was kind of a risky adventure, as the two ladies were quite young and they didn´t have much experience in the field. They didn´t know whether the house would come to life again. The inaugural night was a difficult moment for them. Fortunately, the success went beyond expectations. This is the way Sofia, one of the current co-owners of B.leza, remembers that day:

“We opened in 1995, with a bit of fear because it was something new for us to some extent (…) it was kind of surprising how it became so successful (…) Baile had been falling down in its final years, and we wanted to do something that represented a continuity while making it also clear that there had been a change. (…) I remember the inauguration day, it was 21st December 1995, we went back home to change clothes and come back, and before I phoned Fernanda, a lady that worked there with us in that time. I asked her: “how is it going, Fernanda, how is the house now?” because I was afraid that nobody would come in, those anxieties…she said: “girl, come quickly or you won´t be able to get in”. It was absolutely crowded, things went just great.” (Interview with Sofia co-owner of B.leza)

Exiled from the palace

Unfortunately, nowadays we cannot experience a night in the palace because the owner finally decided to sell the property and B.leza´s soul had to pack up and look for another home. The search was hard, as it was rather difficult to find a new place that could keep up with such high standards. During the period between 2007 and 2012, trying not to leave the B.leza community homeless, the co-owners organized parties that they called B.leza itinerante (itinerant B.leza) in diverse places such as Teatro de São Luis, Teatro da Luz, Maxime or Teatro do Bairro. After some years roaming around the city, B.leza found its new home: an industrial block beside the river Tejo. How to invoke the spirits of the ancient iconic B.leza in a cold and empty diaphanous industrial box with metal serpents running on the ceiling? The staff worked hard to feed the imagination of their loyal members and help them get over the trauma of palace exile.

“Our idea was bringing some elements that could bring people back to the former B.leza. (…) This space was too modern, too cold, and we tried to find elements that could bring in a bit of warmth and a bit of history to the place. So we went to look for velvet for the curtains in a warm colour (…) and old furniture (…) And it seems that we made it, because people say: “oh, those candelabras are from the former B.leza” and they are not! But we got to build that bridge.” (Interview with Sofia, co-owner of B.leza)

Yes, if we go to nowadays´ B.leza, we don´t find ourselves in a palace. Anyway, we shouldn´t feel sad about it because the crystal wall that looks at the Tejo provides us with other kind of luxuries. For example, while dancing in a Sunday matinée we may be amazed by a sight like this one.

As the sun goes down, the lights that let see the silhouette of the bridge 25th April remind the dancers that critical episode in the history of Portugal that changed definitely the destiny of former Portuguese colonies. On the left of the bridge, the illuminated Christo Redentor (Redeeming Christ) seems to look at B.leza and protect the dancing community with his opened arms.

During the day, the walls recently re-painted in deep pink make the new B.leza impossible to remain unseen in a walk by the shore of Tejo in the area of Cais do Sodré. There´s no doubt you will find it if you´re looking for it!

But the most important ritual space is the stage: here the resident band plays every Friday and Saturday, and the living legends and new artists of the Portuguese-speaking countries (and beyond) jump on to display their art. The resident band of B.leza makes people dance every Friday and Saturday: Vaiss Dias (guitar), Cao Paris (drums), Paló Figuereido (bass), Kalú Ferreira (keyboards) and Calú Moreira (voice).

(from www.lisboafricana.com, by Samuel Sequeira)

On Sunday there is an extremely popular Matinée that starts with a dance workshop by some of the best-known teachers of Lisbon, followed by a session guided by DJ Oceano and DJ Sabura.

The organizer of these dancing Matinées is Magda, an incredibly nice and busy young woman (originally from Poland) and a source of never-ending original ideas for new events. She combines her role as producer of music and dance events with her role as doctoral researcher on African music at ISCTE (University of Lisbon).

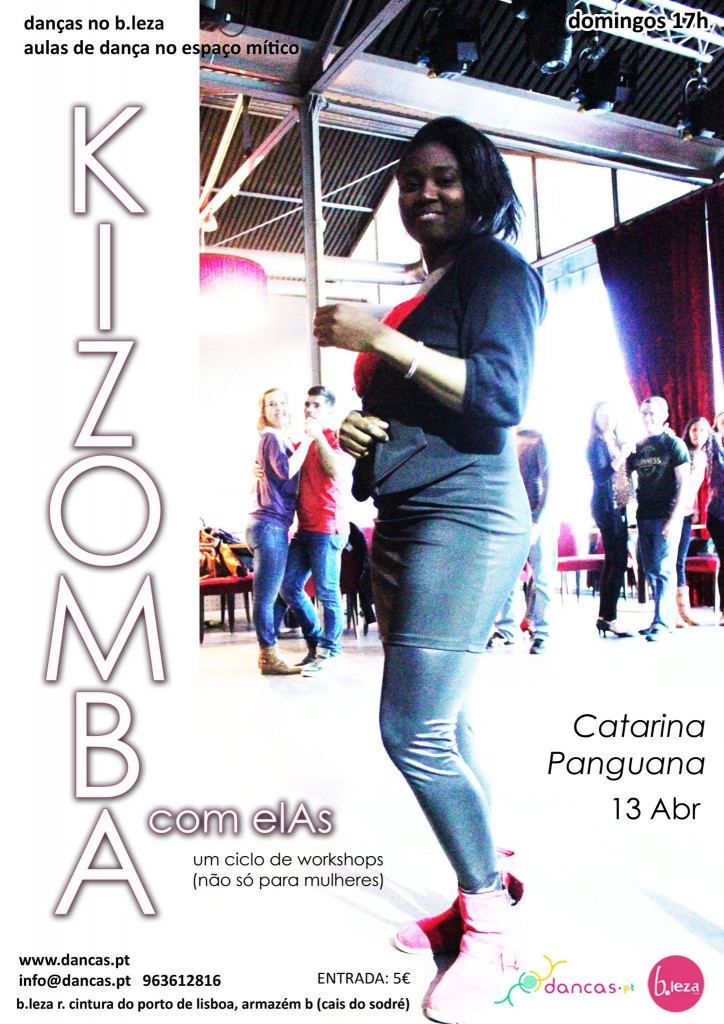

She was responsible for some extremely interesting activities, including a series of colloquia with the main kizomba teachers of Lisbon. Another initiative that she developed and deserves special attention was the series of workshops named Kizomba com Elas (Kizomba with them, a feminine “them”) that intended to bring under the spotlight the work of these female teachers that are usually regarded as secondary actresses in a context where male dancers rule.

B.leza, the democratic dancefloor

One of the most striking aspects of this house is the extraordinary heterogeneity of its clientele. The dancefloor is inhabited by people of all ages, colours, looks, social classes, professions, origins and lifestyles. Indeed, this openness and diversity is one of the main characteristics of B.leza, and it is so because the politics for entering are not restrictive:

“We let everyone in, we don´t have any dress code to get in, people come as they want. If you come from the beach and you wear flip-flops, you get in wearing flip-flops. If you want to come with a shiny dress from head to toe… you just come as you want to come, as you like to come and as you have money to do it (…) There are car parkers, who got some coins today and come to drink their cup of red wine and dance all the night long and everything is ok, or even ministers, judges, the prince of Monaco came here one year ago to dance as any other client, Robert De Niro, Catherine de Neuve…everyone as long as they want to have fun are allowed in.” (Interview with Sofia, co-owner of B.leza)

In this way, the dancefloor becomes a democratic ritual space where social inequalities of everyday life are temporarily suspended. In the words of the classical author Victor Turner, the hierarchical social structure becomes a horizontal communitas during the ritual (Turner 1967). At B.leza nights, the time of the dance is the moment to dream of a better world where everyone is the same…

REFERENCES:

Cidra, Rui (2010a) “B.leza”. In Castelo-Branco, Salwa (dir.) Enciclopédia da Música em Portugal no século XX A-C. Lisboa: Temas e Debates/Círculo de Leitores.

Cidra, Rui (2010b) “Bana”. In Castelo-Branco, Salwa (dir.) Enciclopédia da Música em Portugal no século XX A-C. Lisboa: Temas e Debates/Círculo de Leitores.

Turner, Victor (1969) The Ritual Process. Structure and Anti-structure. New York: Cornell University Press.

Livia Jiménez Sedano is currently member of INET-MD (Instituto de Etnomusicologia-Centro de Estudos em Música e Danca) and her work is being funded by FCT (Fundação para a Ciencia e Tecnologia) of Portugal. She is a collaborator of the Modern Moves Project and will become a full member in September 2015.