One of the most popular songs of the 1950s celebrated the ‘mixed up Siciliano’ who abandoned his native tarantella to ‘learn-a how to mambo’. Dance and style evolve together: even the mozzarella was being forsaken for enchiladas. The result was a fusion of worlds: ‘Mambo Italiano’, as the song’s chorus triumphantly declared. In recent years, ‘Mambo Italiano’ has been reborn: Italy is enjoying a salsa boom, with Milan at the centre of this development.

The new Mambo Italiano exemplifies the history of Afro-Latin dance as one of rebirth and repetition. In the 1940s, ‘mambo’ was the dance style that emerged alongside a new kind of music created by Cuban composers such as Perez Prado. This mambo transmitted the inexplicable exhilarations of modernity. As Celia Cruz sang, ‘mambo es electricidad’ (mambo is electricity). In the 1960s, ‘mambo’ re-emerged in New York as a new way of dancing to Latin music. Repackaged as ‘salsa’, this music still drew on the rhythms of pre-revolution Cuba, which in turn had drawn on the percussive traditions of African slaves on sugar plantations.

Mambo as the New York style of dancing salsa (also called On2) now has a new home in North Italy. Dance schools such as Tropical Gem are legendary in the salsa world for their flair and precision; moreover, the fastest, sharpest and most stylish dancers from Latin America– Juan Matos (from the Dominican Republic), Maykel Fonts (from Cuba- note that he represents the Cuban dance style), and Adolfo Indacochea (from Peru)- have made their home in Milan, while Parma nourishes the talented Italian all male Grupo Alafia. Milan also hosts several international dance festivals dedicated to New York style salsa. Mambo Italiano is once again the rage.

In step with the dance’s popularity, several Italian salsa bands have emerged. Of these, Maxima 79 is the latest and the most successful. Its leader and songwriter Fabrizio Zoro acknowledges salsa’s complex transnational history as his own musical inheritance. ‘Cuban music before the revolution had a lot of influence on the music of New York which at that time included several rhythms such as the cha cha cha, the pilon, the Mozambique, the boogaloo, and the shing-a-ling… The guaganco of the 70s created by Fania [the Latin music conglomerate] was nothing more than the Cuban music of the 40s of Beny Moré, Arsenio Rodriguez, Cachao, Inazio Pineiro, Perez Prado and Xavier Cougat…’

Fabrizio’s musical imagination is fed by two sources: the fertile formative moment of 1940s Cuba, and 1970s New York as a crucible for creative recycling. The Nuyoricans ‘merely improved on a sound that existed earlier but was no longer heard because of the sanctions on Cuba, which, in Cuba, also influenced the way music changed to timba. Many songs of the 70s are covers of the 40s’. From Cuban music to Dominican bachata and salsa brava/ salsa dura (‘strong/ hard salsa’- the music that developed in New York between the late 1960s and the early 1980s), Fabrizio’s historical consciousness combines with a passion for it all. ‘I love to mix it all up.’

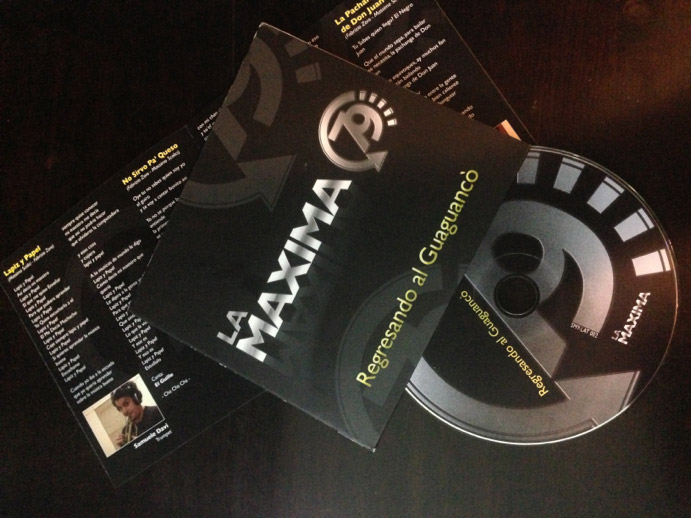

As one of Europe’s most successful Latin DJs, Fabrizio certainly mixes it up on the dance floor at salsa festivals, ensuring that people keep moving till the dawn breaks. Not one to rest on his laurels, he found himself wondering, ‘is it possible to make an album of contemporary salsa with the older sound? Why isn’t anyone doing this?’ Taking up this challenge, he and his friend Massimo Scalici began creating songs under the band name of La Maxima 79 (1979 being the year of Fabrizio’s birth as well part of the decade that gave birth to the salsa he recreates). ‘I wanted to show the world that today one can indeed create a modern salsa album with arrangements and a sound that is typical of yesterday.’

The result is the incredibly successful album Regresando al Guagancò, released last year, although individual songs have been appearing as singles since 2010. As a salsa dancer, I have been part of dance floors going mad for these songs; as a listener, I have been equally engaged by the album’s thematic coherence, historical awareness, percussive energies, and sonic richness. The title, ‘return to the guangancò’ is suggestive: it signals Fabrizio’s desire to return to the musical sounds and arrangements of the 1970s- a project created by ‘a DJ like myself, who for twelve years has been observing what dancers need to be able to dance at their best- with a lot of breaks through which to interpret the music.’ But the ‘guangancò’ he gestures towards is not only its 1970s avatar: it is also the ‘son guaguancò’- ‘a style born with the music of the blind genius, the Cuban Arsenio Rodrigues’- the first to update for modern bands the harmonies of the older plantation genre, the guagancò.

‘An old sound that the dancers of today are always seeking more of’ says Fabrizio of his album- which to drive its point home, even includes two versions of its most popular songs, ‘Pobrecita’ and ‘El Trigueño Cintura’ in ‘old vinyl sound’: the massively favourable reception enjoyed by this album testifies to the paradoxes of the salsa dance floor today. Fully transnationalised, with dancers often travelling every weekend to salsa festivals across the world, there is a deep hunger nevertheless to return to the iconic moments of 1970s New York, to the communities of ‘el barrio’ (the neighbourhood) and ‘la calle’ (the street). Reviving the dance styles of that moment becomes a way to perpetuate and participate in an archive of the body. To consciously create what Fabrizio calls ‘a new album that nevertheless turns back’ is the logical next step.

Replete with tasty cha cha chas, charangas, mambos and guagancòs, nearly all written by Fabrizio and arranged by him and Massimo, the album blurs the distinction between yesterday and now in a manner that replicates the time-dissolving experiences of the dancefloor. This dedicated recreation of a past authenticity makes possible another impossible dream- dancing retro music to a live band that is nevertheless producing original sounds. To experience this ‘Salsagesamtkunstwerk’, I made a pilgrimage to that other shrine of Afro-Latin dance, the Barrio Latino club just off the Bastille in Paris. This beautiful edifice, constructed by none other than Gustave Eiffel, has been hosting salsa and other Latin dance events for the past decade, and it was to celebrate its tenth anniversary that La Maxima 79 were playing there on the 23rd of March this year.

Barrio Latino: a baroque venue which, in its ability to unite, week after week, the highest level of dancers in search of the perfect synthesis of music, movement and style, remains unsurpassed anywhere in the world. The Barrio has always been for me a temple of salsa. I have been drawn to it ever since I first began dancing, and I have literally cut my dancing teeth on its floor. I continue to be struck by this venue’s capacity to support and nourish a dancing crowd that has no historical connection with the world of Spanish colonialism, which produced the musical and kinetic amalgam leading ultimately to ‘salsa’.

Here, dancers from Francophone Africa and the French Caribbean (including several who reveal themselves as of Indo-Caribbean heritage) have their own rhythm (his)stories- and yet they have found in salsa, a style from Latin America, a mode of self-expression and self-fashioning. And at La Maxima’s concert, they were moving to the rhythms of an Italian band whose members ware singing and addressing the crowd in the ‘lingua franca’ of Spanish. This was a fully creolized atmosphere, where ‘creolization’ surpassed the conventional understanding of the term as a new world mixture of European and African— on stage at a certain moment were Italians from Sicily and Lombardy, an elite dancer from Senegal, and the organisers of Barrio’s dance events of North African and Indo-Caribbean lineage respectively (not to forget the researcher-participant from India observing from the floor).

This kind of atmosphere redirects questions about authenticity to issues around the production and circulation of happiness. The desire for authenticity can then be seen as a necessary step towards a historically conscious mode of collective enjoyment. Thus central to the band’s self-projection was the oscillation between their pan-Italian derivation and their lone Cuban member, the singer El Guille, who was asserted to be the ‘soul’ of the band. The need to acknowledge the foundational role of Cuba as the cradle of Afro-Latin sound and spirituality manifests itself in the album’s song ‘Descarga Chango’, a jam session dedicated to Chango/ Santa Barbara, one of the most important Afro-Cuban deities, even as other songs such as ‘Singapore Vibes’ take us on journeys that overlay the older sea routes with the tracks of the jet engine.

As several songs on the album demonstrate, though, Fabrizio created through them a tapestry that weaves together his personal history and that of the music and dance. There are songs dedicated to his late mother (‘Esa Mujer’), to his ex-girlfriend (‘Pobrecita’), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOrfzcA6jzI, to his musical guru (‘Lapiz y Papel’), to his own discovery of salsa brava through the music of Ray Perez (‘El Trigueño Cintura’), and to master reviver of the dance style, the pachanga, his fellow Milanese Juan Matos (‘la Pachanga de Don Juan’). Some songs, such as ‘Habia Cavour’ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1fAWJn7NB0I demonstrate a sublime intertwining of Italian and pan-Latin elements: it describes (verbally and musically) the joys of the cha cha cha alongside the mysterious yet unmistakably Italian refrain ‘Habia Cavour’ (there used to be Cavour), which turns out to be a verbal play on the studio where this album was made, on Milan’s Via Cavour (‘a Via Cavour/ ‘On Via Cavour’).

The most lovable of these Italian-Latino conjunctions is the song ‘No Sirvo Pa’ Queso’ (I’m not used for cheese’) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mBvxbjKMbkw, which describes that most ubiquitous yet potentially overlooked instrument- the guiro or scraper. Sung in the voice of the guiro, the lyrics remind us of the crucial importance of this member of the so-called group of ‘minor percussion instruments’. The chorus asserts, accordingly, that although the whole world may think so, it (the guiro) is not used for cheese- and goes on to add variations on what it actually does to the music: ‘I bring flavor and energy to the guagancò’. Dare we surmise that this totally apt comparison of a scraper to a cheese grater could only have emerged from the imagination of an Italian from Lombardy, one of the provinces that produce Parmesan cheese? As Fabrizio confirms, ‘I wrote it because I always take my guiro to my DJ sessions, and earlier people used to ask, is that a cheese grater?’

The Italian flavour that La Maxima 79 bring to salsa brava is all the more charming for its subtle harmonizing with the rich transnational history that is already folded into the sounds, beats and movements of what we today call salsa. Always reflecting the flow of people dictated by the grand currents of world history, the music continues to draw on new migratory patterns in the post-Cold War Era. As Fabrizio reminds us, ‘there are also many Cubans in Italy from who we have learnt a lot about Caribbean music, making a wonderful connection between Cuban culture and Italian melodies, and Italy is the homeland of melodious music that belongs to the world.’ And as he reminded the audience at Barrio Latino, ‘without music there are no dancers’.

Indeed the story of La Maxima 79’s creation, inspiration and success confirms yet again that Afro-diasporic music and dance moves in surprising ways across the world and under conditions that are completely unpredictable from the perspective of language-based connections between former imperial centres and erstwhile colonies. A Cuban singer paying homage to Chango through songs written by an Italian songwriter, an Italian songwriter paying homage to a Dominican dancer living in Milan who pays homage to a dance style of 1960s New York; a packed dance floor in Paris where dancers from different parts of the Francophone sing with and move to an Italian band singing in Spanish, with the event taking place in a building redolent of Parisian modernism… Through the power of kinetic nostalgia and the pull of the beat, this particular return to the guagancò sounds out the measures of modernity and the continuing potential of rhythm to change the script in a predictable world.

This Moving Story is based primarily on Ananya Kabir’s interview with Fabrizio Zoro, and her experiences of dancing to La Maxima’s music at salsa festivals, salsa parties and en vivo in Paris. All the quotes used within the article are taken from an e-interview with Fabrizio Zoro (13th- 17th April, 2014) and translated from the original Spanish by her.

All photographs used here are by Franck Billaux, Mundo Afro-Latino, Normandy (CHECK), except where specified. Merci, Franck!

We are extremely grateful to Fabrizio Zoro for the precious gifts of his time, music, CD, and words!- and to Wilfrid Vertueux, aka DJ Willy the Viper and Simy Materazzi for facilitating the connection between Fabrizio and Modern Moves. Merci beaucoup/ muchas gracias/ grazie mille!