Our second Moving Group brought together our regulars and some welcome additions for a very special event: a kaizen workshop led by Advisory Board member Kwenda Lima.

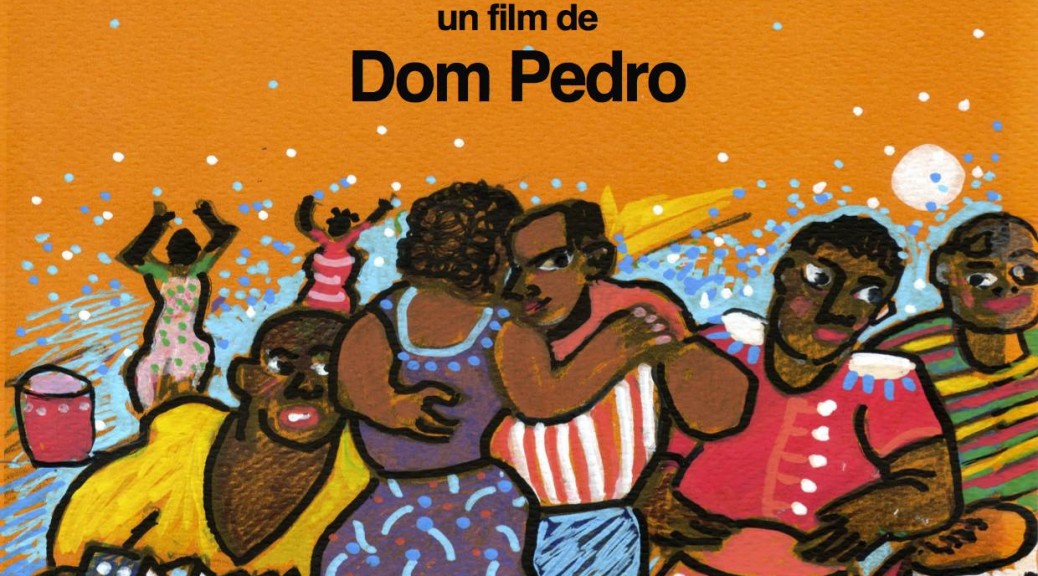

Kwenda, born in that crossroads of rhythm, Cabo Verde, carries in his body the memories and practices of the myriad dance and music forms of his natal archipelago. Internationally renowned as a dancer and instructor of the Angolan social dance kizomba, he has been additionally developing during the past decade his bold and boundary-crossing project, ‘kaizen dance’.

https://www.facebook.com/KwendaLima.KaizenDance

Kwenda’s kaizen dance is a structured yet improvised use of West African dance techniques in non-narrative, movement-based therapy that makes participants reflect on their immersion in modern capitalist life. Drawing on African kinetic principles of call and response and polyrhythm, as well as Eastern philosophical cornerstones of detachment and meditation, Kaizen instigates a mind-body connection that balances the asceticism and individualism of Indic thought with West African spirituality’s intimate relationship with communal, percussion-led movement. Each workshop tailors these raw materials to suit the abilities and size of the group present. Through a unique combination of intuition and analytical intelligence, Kwenda is able to reach out to the group no matter what the precise conditions are: the dimensions of the room, languages shared (or not), and the number of participants.

He certainly rose admirably to the challenges presented by the Moving Group in Somerset House: a group of individuals who are trained to think about and analyse movement, only too aware of our complicities and collusions with capitalism, patriarchy and modernity; a room that turned out to be smaller than anticipated; and the presence of two drummers on the West African dunun whom he was meeting for the first time. In addition, a group of law professors were holding a meeting down the corridor and we were warned that they could find themselves disturbed by the drumming, which turned out to be louder than the events organizing team at King’s had anticipated….

Nevertheless, once the drumming began, a certain magic took over. An astonishing synchronicity emerged between our dancing and the drums, which was later revealed as being the essence of improvisation and call and response—Kwenda had relayed no instructions to the drummer Yahael, who simply took his cue from Kwenda’s initial steps (this is what Yahael explained later is called ‘marking’ the dancer). As the tempo built up, he and his partner drummer Marta branched into different West African rhythms to suit our movements even as we gave back to them our energies in synergistic gratitude.

As dusk fell, the open windows allowed us spectacular views of the spotlit façade of Somerset House and the shadow percussion of the fountains in the courtyard below. An unexpected, transformative beauty emerged through the surreal combination of the drums, our movements, and this setting, a powerful architectural reminder of Britain’s imperial past. Our workshop morphed into a momentary subversion of what J. M. Coetzee laments in his novel, Waiting for the Barbarians, as ‘the time of history’ written by Empire, a temporality which continues to shape and haunt our present.

In keeping with his practice, Kwenda stopped movement three times to lead conversations that ranged from the necessity of detachment and woman’s power as birth-giver (two of his signature topics), to issues introduced by the group’s interests— the possibilities and limitations of partner dance, sweat as a signifier of labour and enjoyment, and dance as engineering: the latter point being taken up by Kwenda as a leitmotif through the workshop. Another leitmotif that has remained with us is his suggestive characterization of the ‘empty space’ in which all creative (self) exploration must take place.

While many participants found the conversation breaks initially inexplicable, a continuing chain of responses and reflections via email reveals Kwenda’s interlacing of talk with movement sequences to have been highly productive as stimulus for reflection and rethinking. In effect, the African drum circle, which is the shape our dancing group assumed, has become a kaizen e-circle…. At the same time, the workshop helped extend Kwenda’s practice. It gave him the opportunity to make us work with live drumming— he wants to collaborate again with the drummers— and to work out how to deal with an overly analytical and therefore resistant group of academics who were secretly longing to release their inner rhythms and stop talking.

Indeed, the Kaizen workshop re-united the two separate senses of the word ‘articulation’— as the connection of our joints, and as the connection of words into sensible speech— allowing us to view it, in fact, as a process of ‘meta-articulation’. A prolonged dinner at Masala Zone Convent Garden encouraged us to process our thoughts further and the Kaizen e-circle also continues to yield ever-richer insights into the relationship between drumming, dancing, talking, and our individual and collective histories.

We are now working on ways to present the findings of this fascinating experiment to the wider public, in conjunction with Kwenda’s inputs.

Watch this (not so empty) space!