Our Moving Conversation #3 brought together Paulo Flores, renowned Angolan musician and songwriter based in Lisbon, and Marissa Moorman, Professor at Indiana University. It definitely was an evening for thinking dancers and dancing thinkers, and plenty of unexpected treats for the enthusiastic audience. Our two high profile personalities in their respective worlds talked to each other about dance, music, diaspora, (post)colonialism, and other shared passions. To complete the transnational web, our resident DJ Willy the Viper from Paris spun a mix of tunes that paid homage to Paulo Flores’ music and that of his Angolan peers as well as their connections to the Antillean genres of zouk and kompa. In keeping with the Afro-Luso theme, the KCL catering team offered vinho verde cocktails and Angolan-inspired ‘salgados’. As Paulo Flores has recently opened a highly acclaimed restaurant in Lisbon, Poema do Semba (named after one of his most beautiful semba songs!), we were more keen than ever to be attentive to this aspect of our event… Read the full report below!

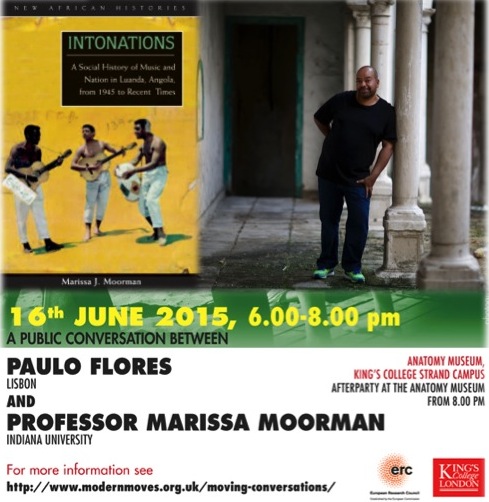

Moving Conversation #3 – 16th June 2015

Report by Ananya Kabir

The final Moving Conversation in our 2014-15 season brought together friends who had been talking to each other for many years already- but perhaps never before in English, in London: Paulo Flores, renowned Angolan musician and songwriter living in Lisbon, and Marissa Moorman, Professor at Indiana University, and Modern Moves advisory board member. Paulo is a leading proponent of the Angolan dance music genre semba, while Marissa’s book, Intonations: A Social History of Music and Nation in Luanda, Angola, has confirmed semba’s key role in the Angolan independence movement; moreover, its conclusion brings the analysis to the present moment via a discussion of Paulo’s music.

Why did Paulo, a member of the decolonized ‘generation of utopia’ (to quote his lyrics), decide to revive this genre? What are the political, social, and cultural contexts for semba’s rise during the decolonizing moment, its fall during the civil war, and its rise again in the age of globalization? What can the ‘secrets of semba’ (in Paulo’s words), tell us about the relationship between civil war, national identity, music, dance, and diaspora? What can the historian tease out of the artiste that his songs perhaps conceal under the veil of poetry? This Moving Conversation revealed all this, and more, to a rapt audience. In true Modern Moves style, they were also treated to dance showcases and a bespoke menu featuring Vinho Verde cocktails and canapés inspired by the Portuguese-speaking world’s signature ‘salgados’ (savouries).

Following the success of Cindy Claes’s and Ziloka’s dance offerings to the guests of our previous Moving Conversation, we opened with a dance creation, ‘Angola: A Dance Portrait’, which we had commissioned from the dancers, our Associated Researcher Francesca Negro from Lisbon and Antonio Bandeira. Their seamless movement from indigenous movements to colonial era carnival dances to the full range of contemporary Angolan social dances, delighted our unsuspecting guests and audience, presented a fitting prelude for a conversation that wove in and out of the traumas of decolonization, war, and diaspora on the one hand, and the participatory joys of social dance and music on the other.

We were plunged into these complexities from the very start of the conversation, with Paulo’s vivid, dream-like recollection of a foundational moment during his first visit to Luanda at the age of five. His Lisbon-based grandmother’s warnings ‘don’t go there, they will kill you’ rang in his ears as he tried to sleep in his Luanda-based father’s bed. Woken up by sudden noise, from the balcony he ‘saw a big colonial pink house with many people on the street, and a military guy whipping a black guy with no shirt on’. Sitting out the mourning period for Angola’s first president Augustinho Neto’s death, he remembered listening to a Muddy Waters record with his father with the sound really low, and wondering if they were doing something wrong.

The blurring between ‘here’ and ‘there’ shaped Paulo’s childhood. ‘I missed Luanda when I was in Lisbon and when I was in Lisbon I felt saudades for Luanda- my mother, aunts, grandmother.’ In Lisbon was the warmth and security of the women of his family; in Luanda, his DJ father with his vast collection of records from all over world—blues, bossa nova, funk, rock, and jazz, and exciting musician friends from Cape Verde, Brazil and Angola. Both were equally shaping influences on his music and lyrics. Another influence, he reiterated throughout the conversation, was ‘the generosity of the people’. And although he didn’t enumerate these, there were three other elements that fed his creativity: the hunger for cosmopolitanism, that fed into the young Paulo through his father’s musical tastes as well as the general Angolan appreciation of zouk music, particularly that of Kassav’ (the subject of course of our previous Moving Conversation); the deep awareness of Lusophone cultural connections between Brazil, Angola, and Cape Verde; and, of course, the city of Lisbon—the ravaged yet radiant muse of his ‘semba urbano’ (urban semba).

Marissa’s astute conversation skills and her deep knowledge of Paulo’s work meant that she could draw out all these issues without making it seem that she had heard it all before! Paulo was obliging and responsive, and a perfect ‘duet’ resulted, which took us through the most important elements in Paulo’s rich career: the decision to take up semba, the continuing necessity of Lisbon for the production of postcolonial Angolan music, the importance of intergenerational (and inter-genre) conversation between Angolan musicians, the need to talk after years of silence and self-censorship through the civil war years.

This duet was supplemented by an irrepressible kinetic vivacity on Paulo’s part. Refusing to be confined to his chair, he treated us to three a capella songs in full- two of which, ‘Boda’ and ‘Poema do Semba’ (in which he even inserted my name! what tribute!) are my personal favourites. Neither did he hesitate to illustrate his points with snatches of song and vocal illustrations of percussion patterns. Joking with the audience in Portuguese and English, he even demonstrated with his body how Angolans would react to a football goal to prove that ‘Angolans always dance’.

It was very satisfying to note how our set up of the Anatomy Museum coincided with Paulo’s improvisations to create stunningly layered effects: as when the video of his song ‘Amba’ flashed up on the screen, demonstrating through stunning monochrome images a capoerista in an Angolan wasteland spliced with Paulo singing, while Paulo himself got up to demonstrate the shared percussive matrix of semba and capoeira. Another memorable moment was when Marissa asked Paulo if people danced to forget or to remember—and he replied with a line from his song, ‘Sassasa’: ‘look at the song of the people—the people of the land who dance without knowing why they do so’ (‘o povo da terra que danca sin saber porque).

As Paulo said, ‘it’s better to sing rather than talk’, and the conversation ended with his singing to his adoring fans two full songs. No doubt energized by that gift, the audience responded with an animated question and answer session in which was re-emphasized some of the most important messages of the Moving Conversation—the striking global proliferation of diverse Angolan music-dance genres (kizomba and kuduro as well as semba), and, in particular, the significance of the body that dances to the song that is sung, to realize the full potential of music as therapy and healing.

Fittingly, the final question asked Paulo for his advice to artistes interested in healing the wounds of conflict through music and dance. Paulo’s response was typical in its humility, prophetic quality, and generosity: ‘I lived in pain for so many years because I could not change anything- I am a musician and people call me the poet of semba- but really what I wanted to do was to change the world- and I felt that at some point my music functioned like balm to people- when I sing about our reality, people put on the music and they feel really full and represented so for me it was a really great privilege.’

Using an anecdote about the camera and exoticisation, he requested the world to approach Angola with intellectual honesty, and to young Angolan artists to also be honest with themselves and listen to their own convictions and their heart. Marissa had the last word though by returning to the forgetting-remembering binary with a third possibility—that people dance Angolan dances to re-member, ‘to reconnect the parts’ as another alternative to ‘memory’ in their search for a viable postcolonial national identity that also participates in the global dance-music sensorium. This was a via media that, I’m sure, the self-declared ‘drunk poet of the senzala’ would approve of.

Following this intensely rewarding conversation, the audience was treated to yet another dance showcase from London’s Studio Afro-Latino student team led by Iris de Brito, and a superb set of semba, kizomba, zouk and kompa by our Paris-based DJ, Wilfrid Vertueux aka DJ Willy the Viper, that illustrated perfectly the transatlantic mix that has gone into Paulo’s life and sensibility. We were also spoilt by a guest set from John Armstrong, London’s veteran of the Afro-decks. As the audience of kizomba and semba lovers circulated with each other and our conversation partners, they confirmed yet again Paulo’s observations on international audiences dancing to his music: ‘when I began playing music for dance at concerts, it had a big impact, it was great, because people were dancing, and that’s the link, really, the way towards big change.’